|

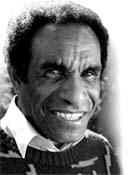

| Saem

Majnep,

Kalam ethnobiologist,

during a visit to

Australian National

University in 1996.

(Photo: Andrew Pawley). |

|

Editorial

In the markets of Marrakech,

Morocco - near where I currently

live - there are seemingly

endless stalls and stores of

medicinal and aromatic plants. As

I walk in this section of the

Medina, or old part of Marrakech,

I often stop to talk with the

herb vendors, who have a wealth

of knowledge about the origin,

preparation and use of the

various botanicals. Occasionally,

one of them will bring out a

medicinal plant book, written in

French, which gives names and

uses that passing tourists can

understand. But for the most

part, they talk of what they have

learned in Arabic from their

fathers and grandfathers or of

knowledge gleaned from Berber

farmers in the Atlas mountains.

|

We imagine this lore has been

passed down from generation to generation

since before the Medieval period, the

golden days of science and pharmacy in

North Africa. When, amidst the curious

tourists, a Moroccan comes seeking a

remedy, it is this oral tradition that

the vendors tap, not the knowledge of

books written by foreigners.

Although we often say that unwritten

knowledge is vulnerable to being lost,

local wisdom has a habit of persisting in

the villages, old towns, markets and

other places where people continue to put

it into practice. One of the plants I

discovered in the souk (traditional

market) of Marrakech is feverfew

(Tanacetum parthenium), a medicinal herb

whose native range extends from southeast

Europe to the Caucasus. In Morocco, it is

known as chajrat maryam, which translates

as Miriam’s tree. Ayad Benjdoudou, a

Marrakech herb vendor, told me that it is

prepared as a tea for reducing fever and

alleviating stomach-aches.

Among the Mixe and other indigenous

peoples of the northern Sierra of Oaxaca,

Mexico – where I had first seen

feverfew – it is known in Spanish as

Santa María, Saint Mary. It is one

example of the large number of plant

species that crossed the Atlantic with

Spanish explorers and immigrants after

the encounter of Europeans and Native

Americans at the end of the 15th century.

José Rivera Reyes, a plant expert from

the Mixe community of Totontepec, told me

that it is used locally for fever and

stomach problems. Although it would take

further historical and linguistic

research to know if feverfew represents a

case of truly similar names and uses for

the same plant in distant parts of the

world, it is a symbol for me of the

transmission through time and space of

not only plant resources, but also the

knowledge linked to them. Both José and

Ayad had learned of the plant and its

uses not through books, but by being

immersed in the stream of spoken

knowledge that flows through their

communities.

Yet Tanacetum parthenium is far from

being absent from the literate tradition.

A look into most modern herbals will tell

you that feverfew is a popular medicinal,

recommended as a stomach tonic and to

relieve indigestion, and recognized as a

traditional remedy for fever. Looking

into sources from the Middle Ages in

Europe, we find feverfew mentioned as a

stomach-ache cure in Matthaéus

Platéarius’(1) Liber de Simplici

Medicina (Book of Medicinal Simples) and

other works.

The existence of these two parallel

and often interconnected ways of

transmitting knowledge brings us to a

dilemma when we seek to return

information gathered in ethnobotanical

studies. Do we give it back in pamphlets,

posters and guidebooks, or do we rely on

new and old forms of communication that

stimulate continued oral transmission?

Those of us educated in a Western or

other literate tradition must ask

ourselves to what extent our interest in

recording oral knowledge is for our own

benefit (intellectual, career, or even

monetary) rather than out of concern for

the cultural survival of local peoples.

We come from a tradition of herbals and

pharmacopeia, while people from other

cultures learn about plants through

story-telling, oral tradition and

word-of-mouth.

There are many reasons for avoiding

the written word when returning results

to communities. We must consider the

ethical implications of such an effort, a

topic taken up in Issue 2 of the People

and Plants Handbook. Committing orally

transmitted wisdom to paper puts

indigenous knowledge on a silver platter

for all to see and consume. Once this

information is in the public domain, it

is difficult for local people to control

its use by other communities, scientists,

governments and commercial enterprises.

Legal instruments such as the Convention

on Biological Diversity promise

protection of genetic resources and

intellectual property rights at national

and international levels, but refusing to

share information remains one of the

important forms of community control over

local knowledge.

We could argue that much of what

communities know about plants is no

secret at all, since many food, timber,

ornamental and even medicinal species are

widely used, and well documented in the

scientific literature. Even if

traditional resource rights are not an

issue, there are other questions that

must be asked about creating local plant

manuals.

First, are they the best way to

communicate results in non-literate or

semi-literate communities? Trish

Shanley(2) notes ‘written give-back

of results to many rural Amazonian

communities is an ineffective mechanism

for the transmission of

information’. She and her colleagues

held interactive workshops in which

participants created posters, plays,

songs and games to bring home their

knowledge of non-timber forest products.

In addition, they put together a booklet

of ‘recipes without words’,

illustrations on the use of Amazonian

medicinal plants designed for

non-literate people. Other researchers

have attempted to put plant lore into

practice, encouraging the cultivation of

useful plants in community gardens,

reforestation with native species and

recovery of traditional modes of plant

use, all activities which encourage

people to remember the merits of local

plants. Technologically oriented

colleagues are experimenting with video,

computerized databases with imbedded

images, geographical information systems

and other multimedia approaches to

ensuring continuity of traditional

knowledge.

Second, are local plant manuals a

priority for community members?

Anthropologists often discover that

plants are popular and non-controversial

subjects for conversation, especially

when compared to topics such as kinship,

religious beliefs and local politics. But

when it comes time for local people to

decide on priorities for community

development, they usually put land

tenure, health care, access to clean

water and education at the top of the

list. Written documents - in the form of

local herbals to improve primary medical

care and botanical texts to enrich

natural history curricula - can help

attain some of these goals, but they

cannot replace land titles, health

clinics, water systems and schools.

Finally, will the manuals transform

the knowledge they are designed to

transmit, and affect non-written modes of

communication? As the anthropologist Jack

Goody(3) notes, ‘... Writing is not

simply added to speech as another

dimension: it alters the nature of verbal

communication’. Some of this

alteration can be positive, if it

involves critical review of what is being

communicated and enrichment with

perspectives of a wide spectrum of

community members. The danger arises when

a written work captures only a meager

part of oral knowledge, represents only

one of many opinions that exist in the

community or introduces plants and

cultural knowledge from outside the

region. Then the contact between local

people and outsiders can generate a

partial, invented culture which persists,

modifying traditions over time.

A historical example of this is found

in De Materia Medica, a treatise on

medicinal plants written by Dioscorides,

a military physician born in Asia Minor

in the 1st century AD. For one and a half

thousand years, physicians and scholars

from across Europe relied heavily on this

herbal, often trying unsuccessfully to

match local floras to the approximately

600 Mediterranean species described by

Dioscorides. As anthropologist Scott

Atran(4) has summarized, ‘the

practice of copying descriptions and

illustrations of living kinds from

previous sources superseded actual field

experience in the schools of late

antiquity. Well into the Renaissance,

scholastic naturalists took it for

granted that the local flora and fauna of

northern and central Europe could be

fully categorized under the Mediterranean

plant and animal types found in ancient

works. Herbals and bestiaries of the time

were far removed from any empirical

base.’ The best way to guarantee

accuracy in local plant manuals and avoid

fossilization of knowledge is to ensure

that any information recorded is as

detailed as possible, and that community

members are committed to a process of

continually reflecting on what has been

written. Plant manuals must undergo the

same process of revision, adaptation and

empirical verification that is an

essential part of oral tradition.

Despite these cautions, I remain

convinced of the merits of creating local

plant manuals. Once the ethical,

intellectual and practical issues have

been addressed, we find that many

communities are enthusiastic about

recording their knowledge. In India, for

example, there is a grassroots movement

to create community biodiversity

registers and seedbanks. The Foundation

for Revitalisation of Local Health

Traditions (see page 12), Navdanya (to be

described in a future issue of the

Handbook) and other Indian

non-governmental organizations promote

community registers that document local

resources and knowledge, serving the

needs of subsistence farmers and not the

interests of non-local commercial

enterprises. In the Solomon Islands,

speakers of various local languages,

including Savo, Roviana, and Areare, are

embarking on a project to create

vernacular botanical dictionaries for

their communities. This process of local

documentation of traditional knowledge is

being coordinated by Barry Evans of the

WWF South Pacific Programme, who is

organizing similar initiatives in Papua

New Guinea and other Melanesian and

Polynesian countries.

After centuries of transmitting

traditional ecological knowledge orally,

why is there a sudden urgency to write it

down? The trend towards documentation is

partly a reaction to the rapid decline in

the diverse languages, environments and

cultures that have contributed to

building the rich empirical knowledge of

nature we find around the world. In a

working conference on endangered

languages, knowledge and environments,

held at the University of California,

Berkeley in October 1996, participants

called attention to the overlap between

cultural, linguistic and biological

diversity – where we find one, we

tend to find the others. Although

opinions vary on what are the causes of

this correlation, close collaboration

between local people and researchers

could play a part in ensuring continued

diversity in the future. Luisa Maffi(5),

organizer of the conference, called

attention to the existence of ‘...

patterns of cultural and linguistic

resistance and knowledge persistence, as

well as efforts to revitalize languages

and cultures that had gone extinct, with

a special focus on maintaining,

recovering and applying knowledge about

traditional resource management

practices’.

Increasing interaction between

community-oriented scientists and local

people is already behind many efforts to

record traditional ecological knowledge.

When they work with outside researchers

on plant resources, community members

discover herbals produced in other parts

of the world and become interested in

creating similar materials for

themselves. This is particularly the case

when some members of the community have

studied in secondary schools and

universities, because formal education

makes them aware of the power of literacy

and of the lack of written materials that

represent their own culture. Responding

to this interest, many community

organizations are supporting the

production of works on natural history.

For example, the Kadazan Dusun Cultural

Association (KDCA) – which

represents Kadazan Dusun people in Sabah,

Malaysia – supports efforts to

document local knowledge of plant and

animals. Joseph Pairin Kitingan(6), KDCA

president, has written that ‘... the

Kadazan Dusun language must live within

the souls of the ... people themselves

through speaking, writing and reading the

language’, a sentiment he further

expresses in the following poem:

Lose your language and you’ll

lose your culture,

Lose your culture and you’ll

lose your identity;

Lose your language and you’ll

lose mutual understanding,

Lose your mutual understanding and

you’ll lose harmony, mutual

support and peace;

Lose your peace and you’ll lose

your brotherhood,

Lose your brotherhood and you’ll

lose your mutual destiny.

It is understandable that losing

control of their destiny ranks high among

the concerns of local people. With the

trend towards globalization of culture,

economy and politics – grounded in

literacy and dominated by a few

international languages – they find

their spoken words have decreasing

influence in the modern world. In

government schools, oral traditions and

ecological knowledge are supplanted by

national curricula. In legal fights for

land tenure and access to resources,

unrecorded knowledge carries no weight.

Environmental and social impact

assessments, requested by governments and

companies eager to proceed with economic

development, are carried out by

consultants who do not have community

benefits in mind. These assessments

rarely assess impact from a local

perspective.

By committing oral knowledge to paper,

local people find a presence in

educational, legal and development fora.

In addition, written accounts of

traditional culture form part of an

appeal to the general public to respect

and recognize the value of local

traditions. This is one of the goals of

the KeKoLdi Wak Ka Koneke Association of

Limón Province, Costa Rica, winner of

the Schultes Award at the 1996 Society

for Economic Botany (SEB) meeting. As

Trish Flaster(7) reports, the Association

and the Bribri and Cabecar peoples it

represents were commended by the Healing

Forest Conservancy ‘... for their

exemplary work in defending their

forests, their traditional lifestyle and

for educating the public about their use

of medicinal plants and world view

through their published text, Taking Care

of Sibo’s Gifts’.

This is just one of several works that

are setting a new standard for recording

ethnobotanical knowledge. The recent

appearance of the first volume of Medical

Ethnobiology of the Highland Maya of

Chiapas, Mexico, written by Elois Ann and

Brent Berlin(8) in collaboration with

Maya field investigators and Mexican

scientists, points to a new

sophistication in understanding

indigenous views of human anatomy,

illness and use of medicinal plants. From

the other hemisphere, we find the works

of Glenn Wightman(9) and his Australian

colleagues, who come from both scientific

and Aboriginal communities. Their book

Traditional Aboriginal Medicine in the

Northern Territories of Australia, which

draws on studies carried out in over

forty-five communities, provides

monographs of 167 plants, animals and

minerals used as remedies. We are waiting

eagerly for the completion of Kalam Plant

Lore, a book about wild plants of the

forests and grasslands of the New Guinea

highlands, being produced through the

collaboration of linguistic

anthropologist Andrew Pawley and the

Kalam natural historian Saem Majnep,

assisted by botanist Rhys Gardner. It

will complement the highly acclaimed

Birds of My Kalam Country, the result of

a collaboration between Saem Majnep(10)

and the late New Zealand ethnobiologist,

Ralph Bulmer.

The spirit of collaboration found in

these works is evident throughout this

issue of the Handbook, which we hope will

be a rich source of ideas for returning

results of ethnobotanical studies and

ensuring they are applied to conservation

and development efforts that benefit

communities. For additional perspectives

on these vital subjects, please look into

the two new Handbook sections we are

inaugurating with this issue. In Advice

from the Field, you will find short

articles by Patricia Shanley and her

colleagues and by Andrew Pawley on

recording and returning data from

ethnobotanical studies. Interviews are

dialogues with innovators in the field,

featuring Glenn Wightman and Mark Plotkin

in this issue.

Recent news of support for the People

and Plants Initiative from the European

Commission (EC) and the John D. and

Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, in

addition to sponsorship by the ODA/WWF

Joint Funding Scheme announced in

mid-1996, means that we have high hopes

of producing the Handbook for another

four years. With continued institutional

support by WWF, UNESCO and the Royal

Botanic Gardens, Kew – and

occasional co-sponsorship by institutions

such as IPGRI – we expect to produce

additional issues in coming years. To

achieve this goal we need your help, so

please keep sending your advice and

perspectives on the subjects we propose

for coming years. /GJM

- Platéarius, M.

1986. Le Livre des Simples

Médecines. Translated and

adapted by G. Malandrin. Paris,

Editions Ozalid et Textes

Cardinoux, Bibliothèque

Nationale.

- See Advice from

the Field, page 33

- See Viewpoints,

page 23.

- Atran, S. 1990.

Cognitive Foundations of Natural

History. Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

- Maffi, L. 1997.

Report on the working conference

‘Endangered Languages,

Endangered Knowledge, Endangered

Environments’. University of

California at Berkeley, 25 - 27

October 1996.

- Kitingan, J.P.

1995. Introduction. In Lasimbang,

R., C. Miller and J. Miller,

editors, Kadazan Dusun Malay

English Dictionary. Kota

Kinabalu, Kadazan Dusun Cultural

Association.

- Flaster, P. 1996.

Society Business. Plants &

People. Society for Economic

Botany Newsletter 10:7.

- See People and

Plants Bookshelf, Multimedia

Center, page 24.

- Aboriginal

Communities of the Northern

Territory. 1993. Traditional

Aboriginal Medicines in the

Northern Territory of Australia.

Darwin, Conservation Commission

of the Northern Territory of

Australia.

- Majnep, S. and R.

Bulmer. 1977. Birds of My Kalam

Country. Auckland, Auckland and

Oxford University Presses.

BACK

Speaking of

Jargon

Applied

ethnobotany, advocacy ethnobotany.

Two terms for an approach – often

promoted in collaborative projects

between local people and researchers

– that seeks to have ethnobotanical

studies support rather than undermine

community development and biodiversity

conservation. Many ethnobotanists have

been compelled to apply the results of

their research when they realize that the

objects of their studies – cultural

knowledge, languages, local people and

biodiversity – are threatened by

environmental destruction and rapid

social and economic change. This change

in consciousness is endorsed by

indigenous, human rights and

environmental groups who claim that

science is not apolitical and that

scientists must be accountable to the

general public.

Biophilia.

Bio- refers to life and -philia to love;

when put together they form biophilia,

which means the love of living things.

Some conservationists – such as S.R.

Kellert and E.O. Wilson, who edited a

book on the subject – hypothesize

that biophilia is an innate or acquired

sensibility in people that explains why

we are attracted to protecting plants,

animals and nature in general.

Endemic.

When used for biological organisms,

endemic describes an organism that grows

or lives in a specific area and has a

restricted distribution. Broad endemics

inhabit a large region (such as the

Amazon), whereas narrow endemics are

confined to small areas, sometimes only a

few square kilometers in size. When using

the term endemic to describe an organism,

it is best to define the region the which

the species grows, such as ‘Phormium

tenax grows in wetlands and is endemic to

New Zealand’. It contrasts with

cosmopolitan, which refers to species

with a worldwide distribution.

Conservation biologists are particularly

interested in endemic species, because

they are particularly vulnerable to

becoming endangered.

Lexicographer,

lexicography, lexicon, lexeme, lexical

item. These are all words

related to dictionaries, their contents

and the people who make them. A lexicon

is a book that contains words of a

language, arranged alphabetically, and

their definitions – what we commonly

call a dictionary. It is also used to

mean the vocabulary used by speakers of a

language. A lexicographer is simply

someone who makes or edits a lexicon, or

dictionary. He or she practices the art

of lexicography, the editing or making of

a dictionary. Lexeme or lexical item,

simply defined, are words – parts of

a lexicon. Lexeme was formerly used by

many ethnobiologists to refer to the

names of plants, animals and other

things: a primary lexeme is a name like

‘owl’, and a secondary lexeme

refers to names like ‘barn

owl’. Most researchers now prefer to

use primary and secondary name instead of

primary and secondary lexeme, because

name is a more common term than lexeme in

the lexicon of most English speakers.

Ambrose Bierce,

an American journalist who was born in

the 19th century, was famous for his

witty definitions. The following entries

are taken from: Bierce, A. 1967. The

Enlarged Devil’s Dictionary. London,

Penguin.

Dictionary.

A malevolent literary device for cramping

the growth of a language and making it

hard and inelastic.

Education.

That which discloses to the wise and

disguises from the foolish their lack of

understanding.

Interpreter.

One who enables two persons of different

languages to understand each other by

repeating to each what it would have been

to the interpreter’s advantage for

the other to have said.

Lexicographer.

A pestilent fellow who, under the

pretense of recording some particular

stage in the development of a language,

does what he can to arrest its growth,

stiffen its flexibility and mechanize its

methods.

Linguist.

A person more learned in the languages of

others than wise in his own.

Lore.

Learning – particularly that sort

which is not derived from a regular

course of instruction but comes of the

reading of occult books, or by nature.

This latter is commonly designated

folk-lore and embraces popularly myths

and superstitions.

BACK

Handbook

Description

This issue is part of a Handbook that

collates information on local knowledge

and management of biological resources,

conservation and community development.

It is intended to encourage exchanges

between colleagues and help them obtain

information from around the world. The

Handbook is designed especially for

people who work in the field: park

managers, foresters, cultural promoters,

and members of non-governmental,

governmental or indigenous organizations.

|

| Argan,

written above in Arabic,

is the Moroccan name of

Argania spinosa

(Sapotaceae), an endemic

tree of Morocco and

Algeria. Oil pressed from

its seeds is used in

local cuisine, cosmetics

and medicine. From:

Sijelmassi, A. 1996. Les

Plantes Médicinales du

Maroc. Casablanca,

Editions le Fennec. |

|

By reporting on

field-based initiatives and

current affairs, we aim to have

an impact on the actions of

researchers and policy-makers as

well. Please send us comments

on the writing style, content and

layout of the Handbook, and

suggestions of new subjects that

could appear in future issues. We

would appreciate receiving any

pamphlets, posters, popular

articles, drawings or other

materials that illustrate the

objectives and results of

programs and projects in which

you are involved. We also request

slides and descriptions of

people, plants and projects for

the Ethnobotanical Portraits

section you will find on pages 36

and 37 of this issue.

|

If you wish to reference this

issue of the Handbook, we suggest the

following citation: Martin, G.J. and A.L.

Hoare, editors. 1997. Issue 3. Returning

Results: Community and Environmental

Education. In: G.J. Martin, general

editor, People and Plants Handbook:

Sources for Applying Ethnobotany to

Conservation and Community Development.

Paris, UNESCO.

When writing to the individuals cited

in this issue, please tell them you

‘saw it in the People and Plants

Handbook’. Letting them know where

you found information about their

organization, publication or project will

help us strengthen our efforts and our

network.

Gary J.

Martin, General Editor, PPH

B.P.262

40008 Marrakesh - Medina

Morrocco;

Fax +212.4.301511

email : 100427.1260@compuserve.com |

Alison L.

Hoore, Associate Editor, PPH

Centre for Economic Botany

Royal Botanic Garden, Kew

Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, UK;

Fax +44.181.3325768

email : a.hoarce@rbgkew.org.uk |

BACK

Leaves of paper :

letters to the editor

24 January 1997

One of my efforts that may be of

interest to readers of the Handbook is

the production of an information system

for local communities to give them access

to resources and information that are

often hard to obtain. I am working with

computer staff and students at Stanford

University to design a Web site called

the Forest Community Source.When the site

is ready, it will provide both local

communities and people who are supporting

their efforts the opportunity to

contribute to a database of information

sources, both on and off the Web. I am

exploring a variety of ways to make this

information database accessible to

communities without Internet access and

computers. Then communities working to

combine forest conservation and

development will be able to exchange

information and to access useful

resources easily.My experience working

with local groups is that there is a

desperate need to integrate ethnobiology

with other aspects of community

development, and that this is a

tremendous challenge. Training ends up

being of no use if it cannot be

integrated into community life, and

sustained over the long term. My hope is

that this information source will help

provide materials, contacts and an

opportunity to exchange experiences that

will strengthen these efforts.

Dominique

Irvine, 632 Dorchester Road, San

Mateo, California 94402-1024, USA;

Fax +1.415.4018757, e-mail nickie@leland.stanford.edu

16 March 1995

I do a lot of my educational work as a

writer; primarily I work with the

interview format as a way of presenting

the information as it is given to me by

the guardians of Puerto Rican botanical

traditions. The idea is to present,

respectfully and elegantly, a mirror of

the knowledge of everyday people who once

learned that their traditional ways are

‘backwards’ or simply

manifestations of their

‘ignorance’. The best example I

have of this in print right now is

¡Hasta los baños te curan! Remedios

caseros y mucho más de Puerto Rico [Even

baths cure! Household remedies and much

more from Puerto Rico].

When this book first came out I was

eager to present the information in a

different format, so I made up 23 short

radio programs each on a theme: healthy

hair and skin, kidney and urinary tract

problems, traditional remedies to ease

childbirth, digestive health and others.

|

| Bundles

of pandanus leaves (Pandanus

sp., Pandanaceae), used

for weaving mats, on sale

in the Suva, Fiji Market. |

|

During each

program, I mentioned the source

(people and town) of all

information used and was careful,

whenever I had the information,

to include ecological facts such

as the status of – and

threats to – the plants

mentioned. My work has included

a number of presentations at

local elementary (primary)

schools. This, besides raising

awareness about the value of the

plants that surround these kids,

is great for self esteem among

the poorer kids who normally

don’t talk in class but

whose grandparents and great

grandparents know all about

plants. Teachers have commented

that certain kids who were super

verbal during my class ‘have

never spoken before without

having been called on!'

|

I also offer a 15-18 hour course

offered at different colleges through the

Continuing Education component of the

University of Puerto Rico. These courses

attract an interesting array of people.

My focus is on: 1) teaching awareness of

the value of Puerto Rico’s botanical

tradition; 2) identifying local plants

and teaching plant identification skills;

3) familiarizing students with

traditional techniques for creating

remedies: teas, syrups, baths, medicinal

soaps, tinctures, etc.; and 4) teaching

methods for gathering useful botanical

information in the field. The students

receive their grade based on this last

part, which is indeed the most important.

I include a sheet describing the work to

be done in the field based on the

students’ own needs, for example, a

health condition that they have not been

able to treat satisfactorily through

conventional means.

I am eager to begin the community

garden project of my dreams. I hope to

spend a good amount of time gaining

practical experience using some of the

traditional agricultural practices

I’m now learning about. I hope that

in some way my public education

activities can contribute to work of the

readers of the People and Plants

Handbook.

Maria

Benedetti, Calle Vista Alegre #314,

Sector Broadway, Mayagúez 00680,

Puerto Rico; Tel. +1.809.8342134, Fax

+1.809.2652880.

14 October 1996

As part of my work in a medicinal

plant garden near Los Tuxtlas in

Veracruz, I have made an inventory of 194

species of plants used as medicine by

rural communities of Catemaco

municipality. The people that live in

this beautiful area have a deep knowledge

of their natural resources, especially

those in the tropical forest. At present,

we are working on a database of local

medicinal plants, and need to add

chemical and pharmacological data to our

information on local usage. In our

botanical garden there is a cultural

center, which in Mexico is called a Casa

de Cultura. We are preparing

environmental education courses and

various public lectures. One of the

objectives of the garden is to return to

communities information obtained from

traditional medicine specialists, because

there is a danger that this valuable

knowledge will be lost. For this reason,

we plan to publish a guide on the

medicinal plants used here, and offer

access to our database on these

resources.I hope that you can put me into

contact with people who can assist me.

Adrian

Garrido Vargas, A.P. 566, C.P. 91000

Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico; Tel./Fax.

+52.294.125748

24 January 1997

The Rain Forest Interpretation Centre

is a new conservation educational

facility situated on the edge of Sepilok

Virgin Jungle Reserve at Sandakan, east

Sabah, Malaysia. It offers a wide range

of information and exhibits on tropical

rain forests; their distribution,

importance, and rate and effects of their

destruction.The Centre aims to make

people more aware of the significance of

the rain forest and the far-reaching

consequences of its destruction, in terms

of impact on the diversity of plant life,

animal life and changes to traditional

societies. Throughout the exhibition the

need for conservation is stressed and

various examples of rain forest

conservation that exist in Sabah are

given, such as permanent forest estates,

national and state parks, ex-situ

conservation and the practice of

sustainable forest management.The

exhibition and facilities at the Centre

(which include a botanical nature trail)

are aimed largely at an audience of

school groups, undergraduates and local

nature clubs.

Lawrence A.

Sibuat, Forest Research Centre,

Forestry Department, P.O. Box 1407,

90008 Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia; Tel.

+60.89.531523, Fax +60.89.531068

21 October 1996

Two years ago I received a pamphlet

about your activities, and I recently

heard that you would like to know about

similar activities that PEMASKY (Programa

de Ecología para el Manejo de Areas

Silvestres Kuna Yala, or Ecological

Program for Managing Kuna Yala Wild

Areas) is carrying out with Kuna

indigenous communities.Five years ago,

PEMASKY began a research program to

compile data by itself. Recently, one of

our activities – focused on the use

of medicinal plants and production of an

interpretive manual for a trail called

Inaigar path – has received outside

support. This 120-page book, which

includes a summary of Kuna cosmovision as

well as drawings and information on the

use of many plants, will be published by

the University of Panama Press at the end

of this year.A related activity –

still without financial support –

that we are considering is the

demarcation of 2 hectares of natural

forest, in which trees of 10 cm diameter

and above will be marked, and their names

and uses recorded. One of the reasons for

doing this is that many Kuna curers, who

are mostly elderly people, never leave

behind any documentation of their

knowledge when they pass away. All of

their mental library is carried away in

their minds, and we are losing valuable

information that the world will never

know unless we document it today for

future generations.

Rutilio

Paredes Martínez, Ethnobotanical

Researcher, PEMASKY, Apartado Postal

2012, Paraíso, Ancon, Panama; Tel.

+507.2257603, Fax +507.2235833

18 September 1996

Forest Tropical Action Program

(Programa de Acción Forestal Tropical,

PROAFT, Asociación Civil) is a

non-governmental organization established

in 1992 to promote the launching, funding

and technical assistance of community

projects that slow deforestation in

tropical zones, find sustainable

management alternatives for natural

resources and improve people’s

standard of living. For us it is

important to have access to the People

and Plants Handbook, because it

represents an opportunity to communicate

easily with people and organizations

around the world that are working on the

same subject, but in many different ways.

I think one of the most interesting

challenges for the Handbook is to involve

people who are working directly in the

field, and relate their experiences and

constraints in developing community

projects.

Silvia del

Amo Rodriguez, Executive Director,

PROAFT, Progreso 5, Colonia del

Carmen, Coyoacán, 04110 Mexico, D.F.

Mexico; Tel. +52.5.6583112, Fax

+52.5.6586324, e-mail proaft@laneta.apc.org

|